How To the Apply Root Cause Analysis Steps

How to apply the steps of the unique Kelvin TOP-SET Root Cause Analysis system from the smallest to the largest incidents.

The TOP-SET system of Root Cause Analysis (RCA) has been refined over many years and leads the world in terms of both its simplicity and effectiveness. There is no other system that matches it for ease of use and comprehensive coverage of all aspects of any incident, from minor to major. Don’t be fooled by thinking that simple systems should only be used for simple investigations. As Leonardo da Vinci wrote, ‘Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication’. We regard that philosophy as fundamental to our aim of ensuring effective investigation and teaching across the world. Our materials are translated into many languages, so complex vocabulary and unnecessary jargon are avoided at all costs.

How are the steps of Root Cause Analysis applied?

A good analysis should fulfil a number of different and important criteria:

1. It should tell the ‘story’ of the incident, so that the reader understands what happened.

2. It should link the incident with the root cause in a series of logical steps, all with evidence.

3. All the issues that contributed to the incident should appear. Those which you can do nothing about or don’t wish to do anything about should be underlined in red to show that they are closed off. They should, however, be included in the analysis to ensure that all aspects of the ‘story’ are recorded.

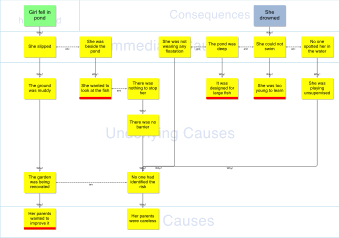

Root Cause Analysis Example:

Look at the RCA diagram below first to see if you can understand what happened.

How did you do?

If you can understand clearly what happened, then the analysis has fulfilled one of its functions.

Now that you have read the analysis, read the short report of the incident below.

The Coquet Island Sea-Kayak Race – Root Cause Analysis example

Gilbert Speirs (on the right) and Andrew Morton (Kelvin TOP-SET senior tutor) have been canoeing buddies since the 1970s. Andrew has entered the Coquet Island race on a number of occasions in the past, but Gilbert has only raced it once before, and won on that occasion, beating Andrew in the process. Andrew won the race three years before, so the competition between these two competitors is keen! Both are British Masters’ Champions in their respective age groups.

The race is a 5-mile race from the harbour at Amble on the east coast of England, out round Coquet Island and back. It’s usually a fairly straightforward race. However, this year was slightly different because there was a gentle easterly breeze bringing in mist from the North Sea. So compasses were essential, and a knowledge of the course useful. Two safety boats were in attendance, and the Mersey class RNLI lifeboat was out on a training run, so the race was well covered.

The organisers confirmed that the normal course would be run, because the island was just visible from the harbour mouth. So, 45 competitors set off at a pace for Coquet Island, with Gilbert in the lead. But, as so often happens, the conditions changed, and once round the island Gilbert and Andrew found that the mainland had disappeared entirely in the thickening mist.

Andrew, who was fifty metres behind Gilbert, left the island and set off in the approximate direction of the harbour. He soon saw some slower paddlers crossing the sea towards the island. This confirmed his track and the harbour soon came into view. But Gilbert disappeared to his right and seemed to be hugging the coast of the island far too long. Was Gilbert’s navigation suspect? Was this a chance to win? Andrew upped the tempo and set off flat out for the finish, expecting Gilbert to catch up and overtake at any moment. But he reached the finish line first, over two minutes ahead of the second paddler, and there was absolutely no sign of Gilbert. What had happened?

Gilbert turned up later, bemused. How was it that he had been in the lead of the race and then found himself overtaking other paddlers? A quick check on the Garmin GPS computer, which he had taken with him, showed a perfect track out and back, with the island marked as a circle. But the Garmin does not mark geographical features, so the circle was not an island, but Gilbert’s track round the island! A safety boat arrived shortly after, with the crew confirming someone had paddled round the island twice. Gilbert had been confused in the mist, hadn’t seen the other slower paddlers coming out from the harbour, and hadn’t bothered to check his compass.

He’s fundamentally a flat-water sprint and marathon paddler, not a sea-kayaker, hence his error. When asked why he didn’t wear his glasses he replied that they often got splashed with spray, and that he liked to rub sweat off his face using his shoulder while holding the paddles. This technique doesn’t work with glasses in the way! So, despite having poor eyesight, he has been happy enough to race without glasses in the past.

Some SMART actions? Yes: always check your compass, and buy some contact lenses!

Should the safety boats have intervened? No, only if a person’s safety was at risk, and Gilbert was perfectly safe paddling round the island as often as he wished!

Andrew is still smiling!

Footnote: The sea is a hazard, and engaging with it is ‘risky’. One woman in the same race capsized in the waves at Coquet, did an Eskimo roll, and continued on to win the ladies event. The photo is of Andrew disappearing below the waves in a similar race off Kerrera in 2015.

Finally, take a look at the root cause analysis steps again and note the following:

Contact Info

Please don't hesitate to get in touch with any questions, to make a booking enquiry or to arrange for a presentation to learn more, and our team will get back to you shortly.

Head Office

info@kelvintopset.com

USA Office

info@kelvintopset.com