Are you curious to see what happens on TOP-SET Senior Investigator and Train...

News

All the latest news and articles from Kelvin TOP-SET

Senior Investigator Course – Glasgow

See below for a selection of photos from the recent Kelvin TOP-SET 3-Day...

Strengthening Cyber Defences: Kelvin TOP-SET Attains Cyber Essentials Certification

In the digital age, where information is a valuable asset, safeguarding...

IOSH Aviation and Aerospace Conference

Kelvin TOP-SET are proud sponsors of this year’s IOSH Aviation and Aerospace...

Improving Aviation and Aerospace Industries

The aviation and aerospace industries are integral to the UK economy and...

New Kelvin TOP-SET Course Venue for 2024

New Kelvin TOP-SET Course Venue for 2024 - The Clayton Hotel, Glasgow. The...

Festive Opening Hours

The UK and US offices will close at 5pm (local time) on Thursday the 21st of...

Recent TOP-SET Course in KL

Enhance Investigation Skills Event Houston

Outline: • Welcome• The principles of investigating any incident• An...

Greater input, greater impact – We at TOP-SET continue our sustainability journey

To support sustainable development across multiple supply chains, Kelvin...

TOP-SET in Dubai

Thank you to all participants and all companies supporting TOP-SET's...

Why Five?

We are sometimes asked how the Kelvin TOP-SET Root Cause Analysis (RCA) system...

TOP-SET Experiences

Derek Hibbard – Global Head of HSSEQ Compliance and Performance Improvement at...

Interviewing for Investigators

Kelvin TOP-SET's Managing Director David Ramsay speaks with Lead Tutor and...

The Big Picture – Perspective and Proportion

One of the biggest problems with our biological makeup is a lack of ability to...

Useful Investigation & Coaching Questions

For readers who have attended a Kelvin TOP-SET Investigators Course, you are...

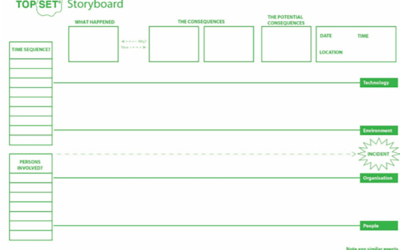

Investigation Tool – The Storyboard

We at Kelvin TOP-SET make use of a Storyboard system for recording the...

How to Standardise Investigations

It’s our business to provide companies with a standardised and structured...

Communication – The Problem?

‘The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken...

What Makes a Good Investigation Leader

If you are heading up an incident investigation, no doubt you are already in a...

Contact Info

Please don't hesitate to get in touch with any questions, to make a booking enquiry or to arrange for a presentation to learn more, and our team will get back to you shortly.